In the spring of 2009 I was staring at my life’s many transitions. I was beginning my 7th season as a wilderness guide for Alaska Alpine Adventures – that was one of my few constants. My wife and I had a new baby on the way, our first, due in October. We were remodeling our house. I was scheduled for major hip surgery in September to correct, of all things, hip displasia. On top of that, I was going to some place in southwest Alaska called Aniakchak – a place unlike any I’d been to before, and one that was no stranger to change, geologically speaking. There was a lot to think about, and a lot to prepare for.

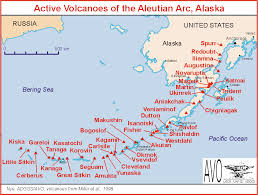

The Aniakchak Volcano in the Aniakchak National Monument is located 450 miles southwest of Anchorage on the Alaska Peninsula. It is one of 40 active volcanoes located along the Aleutian Volcanic Arc, extending from the Alaska Peninsula to the tip of the Aleutian Chain. The Aniakchak Caldera is only accessible by small airplane, boat, or overland on foot. It sees few visitors. While the nearest town, Port Heiden (pop. 102), is only 20 miles west of the caldera, it’s about a half-day of bush flights to get to Port Heiden from Anchorage, and from there, a 2-day journey on foot. Needless to say, you

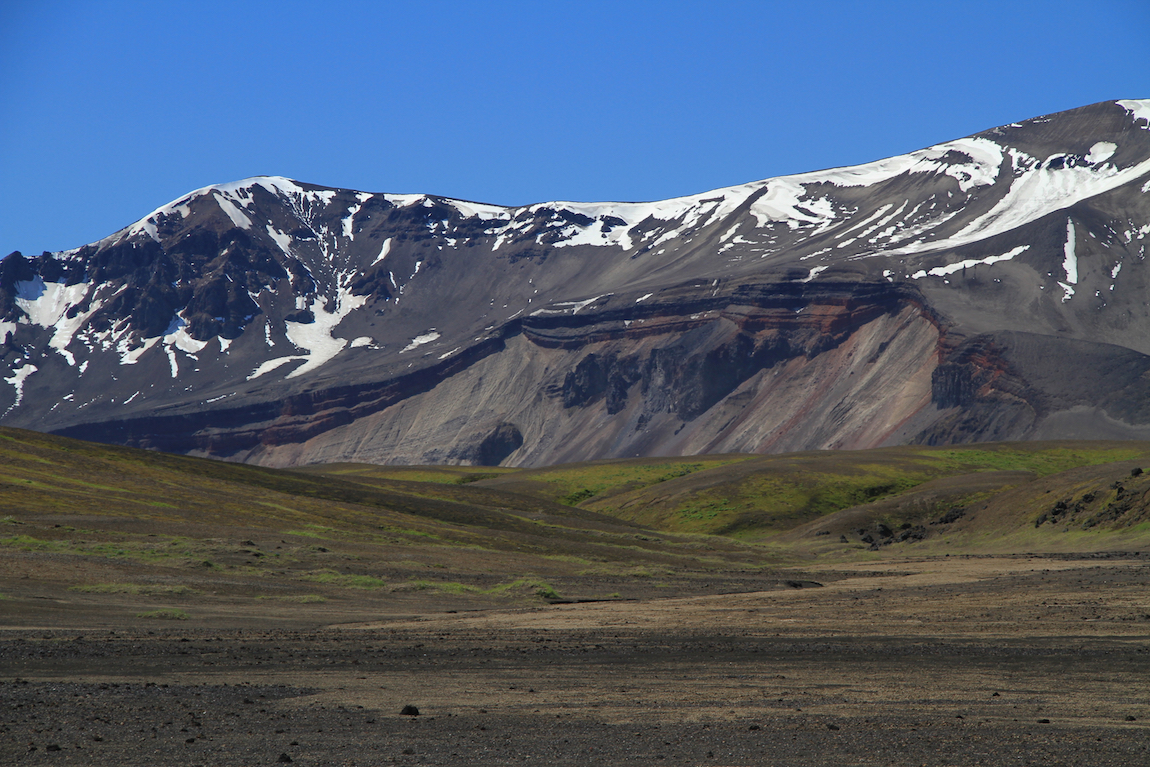

While the volcano itself has been active for over 850,000 years, the Aniakchak Caldera was formed around 3500 years ago when the Aniakchak Volcano erupted and sent pulverized rock, ash, and steam over 80,000 miles into the atmosphere. Coarse pumice and ash traveled north over six hundred miles. Pyroclastic flows (avalanches of hot glowing volcanic ash and rock debris) reached both the Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. With the eruption came the subsequent collapse of the 7000-foot volcano. Having drained its underground magma reservoirs, the volcano collapsed on itself, leaving behind a 3000-foot deep crater. The crater partially filled with water until a breach in the southern portion of the crater rim failed, flooding the landscape with volcanic mud and ash. Today, Surprise Lake is all that remains of the crater lake, and the Aniakchak River flows from its headwaters at the lake to the Pacific Ocean.

Aniakchak has seen additional eruptions since, although never to the extent of the caldera forming event. By the 1900’s life within the caldera flourished. What had been a desolate wasteland was now teaming with diverse flora and fauna, with salmon spawning in Surprise Lake, and caribou dotting the landscape. However, in 1931 the landscape changed again when volcanic activity returned to the crater and a small eruption not only covered the crater floor, but also showered the surrounding landscape up to 40 miles away with ash and debris.

Early in the winter of 2009, Barb & Dean Stewman dropped us a line. They’d traveled with us a few years earlier, on our first trip down the Charley River in Yukon Charley National Preserver, another protected area in Alaska known for its remoteness and shortage of visitors. Barb & Dean were on a quest to see all of the National Park Units in the United States, a substantial challenge to say the least, given the current number of NPS units is 407.

On this trip to Alaska, Barb & Dean were preparing to cover a few of Alaska’s southwest units, specifically Katmai National Park and Aniakchak National Monument. Unlike some travelers on a quest to see all NPS units, they adhered to a stringent rule – they had to do more than set foot in the unit, they had to experience it. Given the experience we’d shared with them on the Charley River, they hired us to take them to Aniakchak, and we were thrilled to be prepare for exploring one of Alaska’s most wild landscapes.

Dan and I had discussed Aniakchak a few times already. In fact, a few years earlier, I had been looking at maps on my computer (which we regularly do here at Alaska Alpine Adventures during the dark days), specifically at the Valley of 10,000 Smokes in Katmai National Park. I scrolled southwest and came across the Aniakchak Caldera. Geographically speaking, the caldera sticks out a bit – a 6-mile wide volcanic caldera in the middle of the Alaska Peninsula. Considering the fact that at this point the Alaska Peninsula spans only 45 miles from the Bearing Sea to the Pacific Ocean, Aniakchak was hard to miss. After a little Google research, I was hooked. According to the National Park website – “Given it’s remote location and challenging weather conditions, Aniakchak is one of the most wild and least visited places in the National Park System.”

Springtime at Alaska Alpine Adventures is always full of preparation, and 2009 was no exception. Every April we make the trip out to our field headquarters in Port Alsworth, Alaska (the gateway community for Lake Clark National Park) to organize and prepare for the coming season. That spring we built guide quarters and a new food preparation room. While we typically spend the days with hammer and nail, the evenings often turn to a glass of bourbon and discussions of adventures in the Alaska wilderness. On a particular evening during that spring trip, the discussion turned to Aniakchak, and I was invited to lead the trip. I’ve been pretty lucky with the trips I’ve guided over the years – in fact this wasn’t my first exploratory trip. But it was the first that I’d researched and executed from start to finish, an achievement that would prove to be even more rewarding in the long run.

In June of 2009, Barb, Dean, my co-guide Seth Plunkett, and I stood in the waiting room of Katmai Air in King Salmon waiting for a weather window to let us into the Aniakchak Caldera. The challenge of getting into Aniakchak is that the crater can create its own weather, and it can be sunny outside of the rim, but filled with fog inside. With enough gear to fill a DeHavilland Beaver floatplane, the one thing we didn’t want was to have to turn around once we got there. At nearly $1000 per hour of flight time, turning a Beaver around isn’t an appealing option. Thankfully the weather cooperated, and were standing on the shores of Surprise Lake in less than 2 hours.

Considered by many a “Life List” trip, our adventures to Aniakchak are typically broken into 2 parts – a few days camped inside the Aniakchak Caldera and 4-5 days rafting the Aniakchak River to its terminus in the Pacific Ocean. It’s a true Alaska wilderness experience, and the chances of seeing other adventurers, or sign there of, is slim. Statistically, Aniakchak National Monument sees 10-15 visitors a year! The caldera is a hiker’s paradise, a trail-less wilderness virtually free of Alaska’s notorious “challenging” vegetation.

With Barb & Dean we explored as many areas of geological significance that we could – from the 1931 eruption site to the sulfurous headwaters of Surprise Lake. Red fox, caribou, and shorebirds visited us regularly. Within the crater walls, one of the most obscure places I had ever explored, I felt as if I was hiking on another planet – completely disconnected from the outside world.

Before we even scratched the surface of fully exploring the caldera, we inflated and loaded our SOAR boats, and made the exciting transition to life on the river. Here we observed the remnants of the volcanic instability, with volcanic debris dotting the landscape and shaping the river. We not only saw brown bears along the way, we also constantly felt their presence, as salmon carcasses littered bear trails formed over centuries of heavy footprints.

The Aniakchak river is fast and splashy for the first half of its 35-mile journey to the ocean, while the second half is calm and meandering. As the river enters Aniakchak Bay, it fans out in a wide delta with beaches stretching for miles. We stopped before the ocean, dragged our boats onto shore, and walked out onto the massive beach on the shore of the bay. No one spoke for some time. It was staggering – the expanse before us and the endless wilderness washing into the Pacific Ocean marked the end of our journey. We had seen so much already, had been so fortunate to experience such a wild place, but to be rewarded with such a magnificent scene felt almost too indulgent. Our last night was spent replaying the trip in our minds, wishing we could go back for more.

The flight back to civilization was simple. In fact, all we had to do was sit in the plane and look out the window. We were passengers again, moving too quickly over the landscape. We wanted nothing more than to ask the pilot to take us back and leave us in the simpler place.

In June of 2014, I found myself standing on the beach of Aniakchak Bay almost 5 years to the day from my first trip. Of course in my life, things were different. My family was growing – Emily was almost 5 and Samantha was due to join us in October. I’d been on many adventures, started a business, and lost and made friends. We’d moved from that remodeled house. Aniakchak had seen 5 harsh winters since 2009. Thousands of gallons of water had made the trip from the caldera to the ocean and countless animals had traversed its landscape. But as I gazed once again at that view across the Pacific, it felt as if nothing or no one had happened there at all. That is the difference between time and life along the Ring of Fire.